Overview

Introduction

Signature schemes allow a signer \(S\) who has established a public key \(pk\) to "sign" a message using the associated private key \(sk\) in such a way that anyone who knows \(pk\) (and knows that this public key was established by \(S\)) can verify that the message originated from \(S\) and was not modified in transit. (Note that the owner of the public key behaves as the sender, which is in contrast to the public-key encryption)

Comparison to MAC:

- Signatures are publicly verifiable: one receiver verifies a signature \(\sigma\) on a given message \(m\) means all other parties will also verify it as legitimate.

- Signatures are transferable: a signature \(\sigma\) on a message \(m\) by a signer \(S\) can be shown to a third party.

- Signatures provide non-repudiation: once \(S\) signs a message, the signer cannot later deny having done so. But MAC cannot provide that property.

- Signatures are much slower: MAC is roughly 2-3 orders of magnitude more efficient than digital signatures.

Definitions

A digital signature scheme consists of three probabilistic polynomial-time algorithms \((Gen,Sign,Vrfy)\) such that:

- The key-generation algorithm \(Gen\) takes as input a security parameter \(1^n\) and outputs a pair of keys \((pk,sk)\). These are called the public key and the private key, respectively. We assume that pk and sk each has length at least \(n\), and \(n\) can be determined from \(pk\) or \(sk\).

- The signing algorithm \(Sign\) takes as input a private key \(sk\) and a message \(m\) for some message space. It outputs a signature \(\sigma\), and we write this as \(\sigma\leftarrow Sign_{sk}(m)\).

- The deterministic verification algorithm \(Vrfy\) takes as input a public key \(pk\), a message \(m\) and a signature \(\sigma\). It outputs a bit \(b\), with \(b=1\) meaning valid and \(b=0\) meaning invalid. We write this as \(b:=Vrfy_{pk}(m,\sigma)\).

It is required that except with negligible probability over \((pk,sk)\) output by \(Gen(1^{n})\), it holds that \(Vrfy_{pk}(m,Sign_{sk}(m))=1\) for every legal message \(m\).

The Hash-and-Sign paradigm

Similar with hybrid encryption, it is possible to obtain the functionality of digital signatures at the symptotic cost of a private-key operation, at least for sufficient long messages. This can be done using the hash-and-sign approach.

Let \(\Pi=(Gen,Sign,Vrfy)\) be a signature scheme for messages of length \(\ell(n)\), and let \(\Pi_{H}=(Gen_{H},H)\) be a hash function with output length \(\ell(n)\). Construct signature scheme \(\Pi'=(Gen',Sign',Vrfy')\) as follows:

- \(Gen'\): on input \(1^n\), run \(Gen(1^{n})\) to obtain \((pk,sk)\) and run \(Gen_{H}(1^{n})\) to obtain \(s\); the public key is \(<pk,s>\) and the private key is \(<sk,s>\).

- \(Sign'\): on input a private key \(<sk,s>\) and a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^*\), output \(\sigma \leftarrow Sign_{sk}(H^{s}(m))\).

- \(Vrfy'\): on input a public key \(<pk,s>\), a message \(m\in\{0,1\}^*\), and a signature \(\sigma\), output 1 if and only if \(Vrfy_{pk}(H^{s}(m),\sigma)=1\).

If \(\Pi\) is a secure signature scheme for messages of length \(\ell\) and \(\Pi_{H}\) is collision resistant, then the above construction is a secure signature scheme (for arbitrary-length messages).

RSA signatures

Plain RSA

Let \(GenRSA\) be as in the text. Define the plain RSA signature scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\) run \(GenRSA(1^{n})\) to obtain \(<N,e,d>\). The public key is \(<N,e>\) and the private key is \(<N,d>\).

- \(Sign\): on input a private key $ sk=<N,d>$ and a message \(m\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), compute the signature \(\sigma:=[m^{d}~mod~N]\).

- \(Vrfy\): on input a public key \(pk=<N,e>\), a message \(m\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), and a signature \(\sigma\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), output 1 if and only if \(m=[\sigma ^{e}~mod~N]\).

The plain RSA signature scheme is vulnerable to the following two types of attack:

- No-message attack: the forgery use the public key alone, without obtaining any signatures from the legitimate signer. The attacker choose a uniform \(\sigma \in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\) and compute \(m:=[\sigma ^{e}~mod~N]\). Then output the forgery \((m,\sigma)\).

- Forging a signature on an arbitrary message: when the adversary can obtain two signatures from the signer, the signature \(\sigma:=[\sigma_{1}\cdot \sigma_{2}~mod~N]\) is a valid on message \(m=m_{1}\cdot m_{2}~mod~N\).

RSA-FDH and PKCS #1 v2.1

Let \(GenRSA\) be as in the text. Construct the RSA-FDH signature scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\) run \(GenRSA(1^{n})\) to obtain \(<N,e,d>\). The public key is \(<N,e>\) and the private key is \(<N,d>\). Also, a key is generated to specify a function \(H:\{0,1\}^{*}\rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\).

- \(Sign\): on input a private key \(sk=<N,d>\) and a message \(m\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), compute the signature \(\sigma:=[H(m)^{d}~mod~N]\).

- \(Vrfy\): on input a public key \(pk=<N,e>\), a message \(m\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), and a signature \(\sigma\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), output 1 if and only if \(\sigma^{e}=[H(m)~mod~N]\).

The hash function should satisfy that:

- \(H\) should be hard to invert.

- \(H\) does not admit multiplicative relations.

- It is hard to find collisions in \(H\).

There is no known way to choose \(H\) so that the above construction can be proven secure. But it is possible to prove security if \(H\) is modeled as a random oracle that maps its inputs uniformly onto \(\mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\). The scheme in this case is called the RSA full-domain hash (RSA-FDH) signature scheme.

The RSA PKCS #1 v2.1 standard includes a signature scheme that can be viewed as a variant of RSA-FDH. The standard defines a scheme in which the signature on a message depends on a salt (i.e., a random value) chosen by the signer at the time of signature generation.

Signatures from the Discrete-Logarithm problem

The Schnorr signature scheme

An identification scheme is an interactive protocol that allows one party to prove its identity (i.e., to authenticate itself) to another.

The party identifying herself is called the "prover", and the party verifying the identity is called the "verifier". Successful execution of the identification protocol convinces the verifier that it is communicating with the intended prover rather than an imposter.

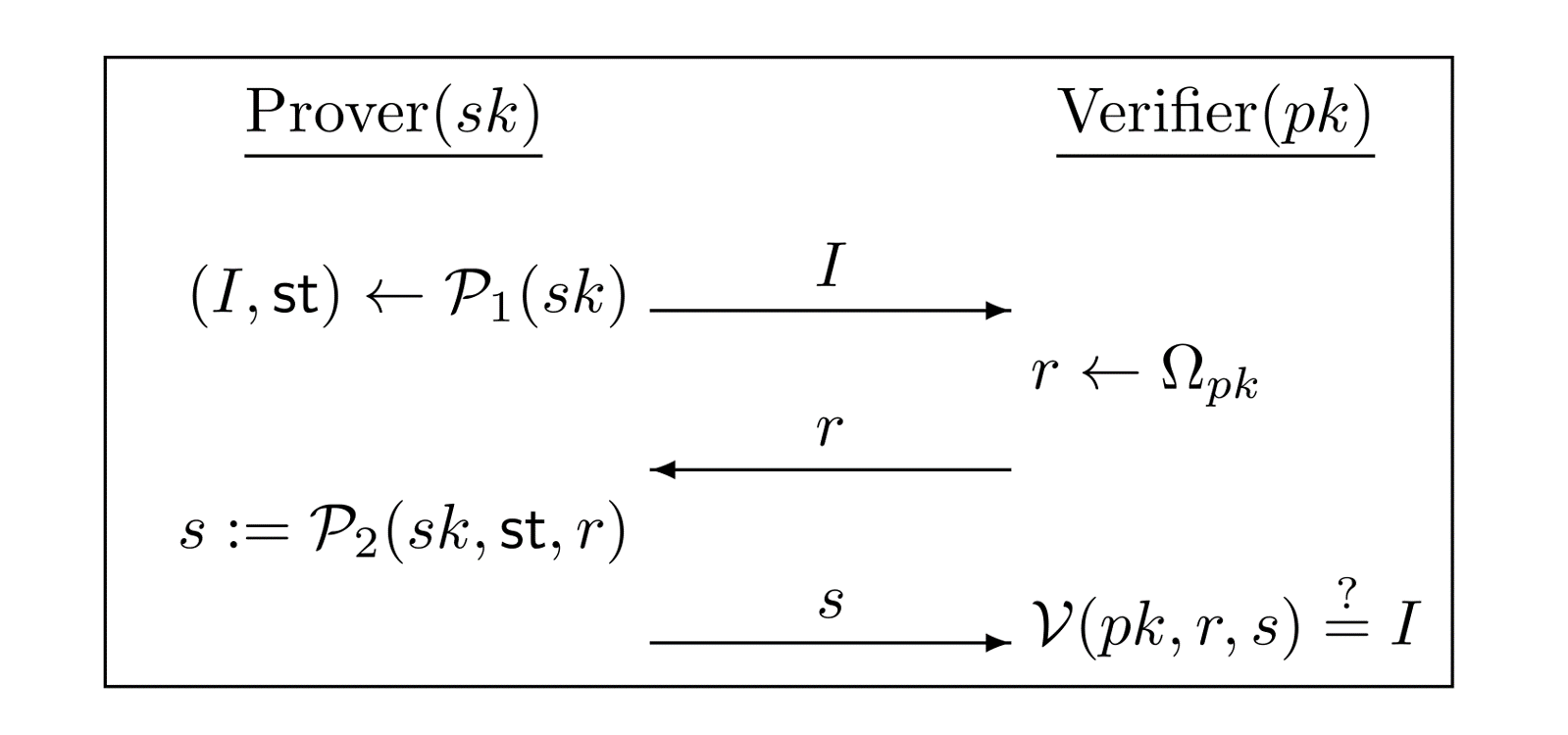

Three-round identification scheme

A three-round identification scheme is shown as the following figure. \(\mathcal{P}_{1}\), \(\mathcal{P}_{2}\) are two algorithms used by the prover and \(\mathcal{V}\) is the algorithm used at the verifier's side. \(\Omega_{pk}\) is a set defined by the prover's public key \(pk\).

Fiat-Shamir transform

The Fiat-Shamir transform provides a way to convert any interactive identification scheme into a non-interactive signature scheme. The basic idea is for the signer to act as a prover, running the identification protocol by itself.

Let \((Gen_{id},\mathcal{P}_{1},\mathcal{P}_{2},\mathcal{V})\) be an identification scheme, construct a signature scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\), simply run \(Gen_{id}(1^{n})\) to obtain keys \(pk,sk\).

- \(Sign\): on input a private key \(sk\) and a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^{*}\), do:

- Compute \((I,st)\leftarrow \mathcal{P}_{1}(sk)\).

- Compute \(r:=H(I,m)\).

- Compute \(s:=\mathcal{P}_{2}(sk,st,r)\).

- Output the signature \((r,s)\).

- \(Vrfy\): on input a public key \(pk\), a message \(m\), and a signature \((r,s)\), compute \(I:=\mathcal{V}(pk,r,s)\) and output 1 if and only if \(H(I,m)=r\).

Let \(\Pi\) be an identification scheme, and let \(\Pi'\) be the signature scheme that results by applying the Fiat-Shamir transform to it. If \(\Pi\) is secure and \(H\) is modeled as a random oracle, then \(\Pi'\) is secure.

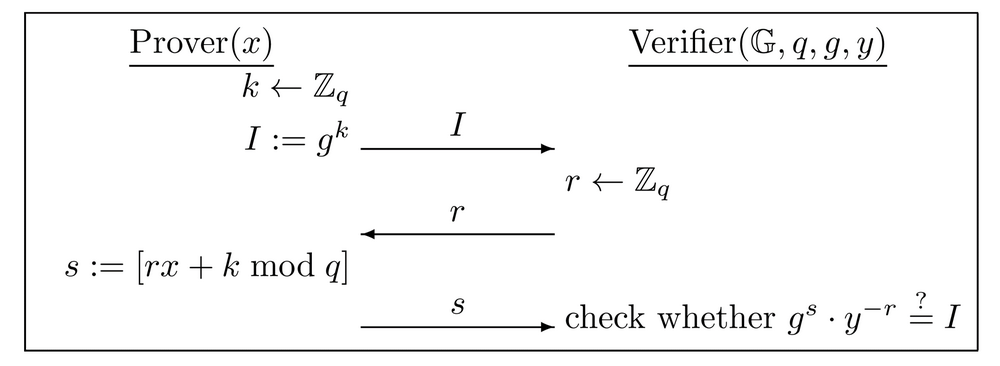

Schnorr identification scheme

The Schnorr identification scheme is based on hardness of the discrete-logarithm problem. An execution of the Schnorr identification scheme is shown as the following figure. Note that the cyclic group \(\mathbb{G}\), its order \(q\) and a generator \(g\) are generated by a polynomial-time algorithm \(\mathcal{G}\).

If the discrete-logarithm problem is hard relative to \(\mathcal{G}\), then the Schnorr identification scheme is secure.

By applying the Fiat-Shamir transform to the Schnorr identification scheme, the Schnorr signature scheme is obtained as follows:

- \(Gen\): run \(\mathcal{G}(1^{n})\) to obtain \((\mathbb{G},q,g)\). Choose a uniform \(x\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and set \(y:=g^x\). The private key is \(x\) and the public key is \((\mathbb{G},q,g,y)\). Also, generate a key to specify a function \(H:\{0,1\}^{*}\rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{q}\).

- \(Sign\): on input a private key \(x\) and a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^*\), choose uniform \(k\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and set \(I:=g^k\). Then compute \(r:=H(I,m)\), followed by \(s:=[rx+k~mod~q]\). Output the signature \((r,s)\).

- \(Vrfy\): on input a public key \((\mathbb{G},q,g,y)\), a message \(m\), and a signature \((r,s)\), compute \(I:=g^{s}\cdot y^{-r}\) and output 1 if \(H(I,m)=r\).

DSA and ECDSA

The Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) and Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) are based on the discrete-logarithm problem in different classes of groups. They are both included in the current Digital Signature Standard (DSS) issued by NIST.

Let \(\mathbb{G}\) be a cyclic group of prime order \(q\) with generator \(g\), both schemes can be seen as constructing from the following identification scheme:

- The prover chooses uniform \(k\in \mathbb{Z}_{q}^{*}\) and sends \(I:=g^k\).

- The verifier chooses and sends uniform \(\alpha,r\in \mathbb{Z}_{q}\) as the challenge.

- The prover sends \(s:=[k^{-1}\cdot (\alpha + xr)~mod~q]\) as the response.

- The verifier accepts if \(s\ne 0\) and \(g^{\alpha s^{-1}}\cdot y^{rs^{-1}}=I\).

The DSA/ECDSA signature scheme are constructed by "collapsing" the above idnetification scheme into a non-interactive algorithm in a different way from Fiat-Shamir transform. The construction is as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\), run \(\mathcal{G}(1^{n})\) to obtain \((\mathbb{G},q,g)\). Choose uniform \(x\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and set \(y:=g^x\). The public key is \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,y>\) and the private key is \(x\). Also generate two functions \(H:\{0,1\}^{*}\rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_q\) and \(F:\mathbb{G}\rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_q\).

- \(Sign\): on input the private key \(x\) and a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^*\), choose uniform \(k\in \mathbb{Z}_{q}^{*}\) and set \(r:=F(g^{k})\). Then compute \(s:=[k^{-1}\cdot (H(m)+xr)~mod~q]\). (if \(r=0\) or \(s=0\) just start again with a new \(k\)). Output the signature \((r,s)\).

- \(Vrfy\): on input a public key \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,y>\), a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^*\), and a signature \((r,s)\) with \(r,s\ne 0~mod~q\), output 1 if and only if \(r=F(g^{H(m)\cdot s^{-1}}y^{r\cdot s^{-1}})\).

The function \(H\) is a cryptographic hash function; the function \(F\) depends on the group \(\mathbb{G}_m\), which in DSA is defined as \(F(I)=[I~mod~q]\), and is defined as \(F((x,y))=[x~mod~q]\) in ECDSA. Also pay attention that the signer should choose a uniform \(k\in \mathbb{Z}_q^{*}\) when computing a signature.

Certificates and public-key infrastructures

Certificates

Definition

In concrete, assuming a party Charlie has generated a key-pair \((pk_{C},sk_{C})\) for a secure digital signature scheme. Further another party Bob has also generated a key-pair \((pk_{B},sk_{B})\) and Charlie knows that \(pk_B\) is Bob's public key. Then Charlie can compute the signature \(cert_{C\rightarrow B}=Sign_{sk_{C}}(\mathrm{'Bob's~key~is~} pk_{B}\mathrm{'})\) and give this signature to Bob. \(cert_{C\rightarrow B}\) is called a certificate for Bob's key issued by Charlie.

When Bob wants to communicate with some other party Alice who already knows \(pk_C\), Bob can send \((pk_{B},cert_{C\rightarrow B})\) to Alice, who can then verify that \(cert_{C\rightarrow B}\) is indeed a valid signature on the message "Bob's key is \(pk_{B}\)" with respect to \(pk_{C}\). If verification succeeds, and Alice trusts Charlie, she can accept \(pk_B\) as Bob's legitimate public key. Note that all the communication between Bob and Alice can occur over an insecure and unauthenticated channel.

Details of a certificate

Looking at the details of the certificate in Windows OS or Firefox Browser, we can see the digital certificate contains the following elements:

- Certificate

- Version: the version of the digital certificate. (X.509 v1, X.509 v2, X.509 v3)

- Serial number: each certificate has a unique serial number.

- Valid from: the certificate is not valid before that time.

- Valid to: the certificate is not valid after that time.

- Issued to (subject): the owner information of the certificate, including the name of owner, public key, etc.

- Issued by (Issuer): whom this certificate is signed by (the root CAs are themselves).

- Extensions: key usage, constraints, etc.

- Certificate signature algorithm: hash algorithm & public-key encryption algorithm.

- Certificate fingerprint: the encrypted hash value of the certificate, which is used to check the integrity of the certificate. (How the hash value is calculated: TBSCertificate content of the certificate. See https://stackoverflow.com/questions/12645128/certificate-hash-checking)

Public-key infrastructure (PKI)

Types

The Public-key infrastructure (PKI) enables the widespread distribution of public keys. Some types of PKI are described as follows:

- A single certificate authority. The simplest PKI assumes a single certificate authority (CA) who is completely trusted by everybody and who issues certificates for everyone's public key. Anyone who wants to rely on the services of the CA would have to obtain a legitimate copy of the CA's public key \(pk_{CA}\). This step must be carried out in a secure fashion, i.e., \(pk_{CA}\) must be distributed over an authenticated channel (e.g. via physical means like USB, bundle the public key with softwares). Only one CA is not very practical: it is unlikely for everyone to trust the same CA, the CA is a single point of failure for the entire system, it is inconvenient for all parties to have to contact only one CA, etc.

- Multiple certificate authorities. A party Bob who wants to obtain a certificate can choose which CA(s) he wants to issue a certificate. And a party Alice, who is presented with multiple certificates, can choose which CA's certificates she trusts. In this way, the security of Alice's communication is ultimately only as good as the least-secure CA she trusts.

- Delegation and certificate chains. Certificate chains can alleviate the burden on a single CA, but add more points of attack in the system. Say Charlie who acting as a CA issues a certificate \(cert_{C\rightarrow B}\)for Bob, and trust him to issue other certificates at the same time. Then, Bob can issue a certificate \(cert_{B\rightarrow A}\) for Alice. When Alice wants to communicate with Dave who knows \(pk_{C}\), she can send \(pk_{A},cert_{B\rightarrow A},pk_{B},cert_{C\rightarrow B}\) to Dave. If Dave trusts Charlie to issue certificates only to trustworthy people, then Dave may accept \(pk_A\) (need to certificate recursively). We say that Charlie is, in effect, delegating his ability to issue certificates to Bob.

- The "web of trust" model. This model is a fully distributed model with no central points of trust. In this model, anyone can issue certificates to anyone else, and each user has to make their own decision about how much trust to place in certificates issued by other users. So users need to collect both public keys of other parties and certificates on their own public key. This model might work well for users encrypting their email, but it is not appropriate for settings where security is more critical or for the distribution of organizational public keys.

PKI in practice

In practice, there are many root CAs in different countries, whose certificates validate themselves. And each CA will delegate their authority to some trust entities. For users, they have a certification database enlisting the trusted CAs. E.g., the certification database in Windows OS containing their expiration date, encryption algorithm, public key and so on, as the following figure shows.

The things described above form a disclosure of the certification chain. A simple example of certification scheme is shown as the following illustrations:

For Windows OS, the trust CAs could be preinstalled in the OS to ensure its security. Some softwares may also include their own CAs. For flexibility, CA could also be installed manually, but this could be dangerous. In some other situations, the trust CAs might be written into chips directly, or they might be installed from hardware.

Invalidating certificates

The certificates should generally not be valid indefinitely. In some scenerios, we need a way to render previously issued certificates invalid.

- Expiration. One method is to include an expiry date as part of the certificate. But this is a very corase-grained solution.

- Revocation. The CA can explicit revoke the certificate to make certificates become invalid as soon as possible. One way is to include a unique serial number in every certificate. And the CA needs to widely distribute a signed certificate revocation list (CRL) with the serial number of all revoked certificates and current date.

SSL/TLS

Overview

Say two people, Alice and Bob, want to communicate with each other in a public and unauthenticated channel. Both of them have certificates from the same root CA. The communication between them can use each other's public key to encrypt and use their own private key for signature, after sending and checking the certificates in advance. But this way could be time-consuming, and getting a certificate might be difficult sometimes. TLS/SSL offers a way to solve the two problems.

TLS is the protocol used by the browser any time when connect to a website using https rather than http. It is a standardized protocol based on a precursor called SSL (Secure Socket Layer).

The requirement of certificates differ from applications. In HTTPS and FTPS protocol, only the certificate of the server is required (one-way verification). And for some more straight situations like Web banking, the certificates from both sides are required (mutual verification).

TLS allows a client and a server to agree on a set of shared keys and then to use those keys to encrypt and authenticate their subsequent communications. It consists two parts: a handshake protocol that performs authenticated key exchange to establish the shared keys, and a record-layer protocol that uses those shared keys to encrypt/authenticate the parties' communication.

The hand-shake protocol

At the outset of the protocol, the client \(C\) holds a set of CA's public keys \({pk_{1},\dots,pk_{n}}\), and the server \(S\) has a key-pair \((pk_{S},sk_{S})\) for a KEM along with a certificate \(cert_{i\rightarrow S}\) issued by one of the CAs whose public key \(C\) knows. To connect to \(S\), the parties run the following steps:

- \(C\) begins by sending a message to \(S\) that includes information about the versions of the protocol supported by the client, the ciphersuites supported by the client (the hash functions or block ciphers the client allows) and a uniform value \(N_{C}\).

- \(S\) responds by selecting the latest version of the protocol it supports as well as an appropriate ciphersuite. It also sends its public key \(pk_{S}\), its certificate \(cert_{i\rightarrow S}\) and its own uniform value \(N_{S}\).

- \(C\) checks whether one of the CA's public keys \(pk_i\) matches the CA who issued \(S\)'s certificate, also checks whether it has not expired or been revoked. If so, \(C\) verifies the certificate and learns that \(pk_{S}\) is \(S\)'s public key. Then it runs \((c,pmk)\leftarrow Encaps_{pk_{S}}(1^{n})\) to obtain a ciphertext \(c\) and a so-called pre-master key \(pmk\) (used to derive a master key \(mk\) using a key-derivation function applied to \(pmk,~N_{C} ~\textrm{and}~N_{S}\), which is then used by the client in a pseudorandom generator to derive four keys \(k_{C},k_{C}^{'},k_{S},k_{S}^{'}\)) and then send \(c\) to the server. Finally, \(C\) computes \(\tau_{C}\leftarrow Mac_{mk}(transcript)\), where \(transcript\) denotes all messages exchanged between \(C\) and \(S\) thus far, and send \(\tau_{C}\) to \(S\).

- \(S\) computes \(pmk:=Decaps_{sk_{S}}(c)\), from which it can derive \(mk\) and \(k_{C},k_{C}^{'},k_{S},k_{S}^{'}\) as the client did. If \(Vrfy_{mk}(transcript,\tau_{C})\ne 1\), then \(S\) aborts (If this happen, choose a uniform \(pmk\) and continue running using that value, which can prevent Bleichenbacher-style attacks). Otherwise, it sets \(\tau_{S}\leftarrow Mac_{mk}(transcript')\), where \(transcript'\) denotes all the messages exchanged between \(C\) and \(S\) thus far. Then \(S\) sends \(\tau_{S}\) to \(C\).

- If \(Vrfy_{mk}(transcript',\tau_{S})\ne 1\), the client aborts.

At the end of a successful executin of the handshake protocol, \(C\) and \(S\) share a set of four symmetric keys \(k_{C},k_{C}^{'},k_{S},k_{S}^{'}\).

TLS 1.2 supports two KEMs: a CDH/DDH-based KEM, or the RSA-based encryption scheme PKCS #1 v1.5.

For situations need mutual verification, the handshake process is similar, except that the server will also check the identity of the user before sharing the symmetric key.

The following is an illustration of SSL handshake process:

The record-layer protocol

once keys have been agreed upon by \(C\) and \(S\), the parties use those keys to encrypt and authenticate all their subsequent communication. \(C\) uses \(k_{C}\) to encrypt and \(k_{C}^{'}\) to authenticate all messages it sends to \(S\); \(S\) uses \(k_{S}\) and \(k_{S}^{'}\) to encrypt and authenticate all the messages it sends. Sequence numbers are used to prevent replay attacks.

Pseudocode

Client

1 | //construct communication with server |

Server

1 | //construct connection with client |

References

- https://www.zhihu.com/question/22260090/answer/648910720

- Jonathan Katz, Yehuda Lindell. Introduction to Modern Cryptography, Second Edition.

- https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/34322643

- https://blog.csdn.net/carolzhang8406/article/details/79458206

- https://www.jianshu.com/p/df935a45c7e0

- https://blog.csdn.net/adeyi/article/details/8556170

- https://www.zhihu.com/question/24294477

- https://www.cnblogs.com/JeffreySun/archive/2010/06/24/1627247.html

- https://blog.csdn.net/dcz1001/article/details/22192655

- https://www.cnblogs.com/jifeng/archive/2010/11/30/1891779.html