Math related with public-key encryption

Diffie-Hellman problems

Fix a cyclic group \(\mathbb{G}\) and a generator \(g\in \mathbb{G}\). Given elements \(h_{1},h_{2}\in \mathbb{G}\), define \(DH_{g}(h_{1},h_{2})=g^{log_{g}h_{1}\cdot log_{g}h_{2}}\). That is, if \(h_{1}=g^{x_{1}}\) and \(h_{2}=g^{x_{2}}\) then \[ DH_{g}(h_{1},h_{2})=g^{x_{1}\cdot x_{2}}=h_{1}^{x_{2}}=h_{2}^{x_{1}} \]

The computational Diffie-Hellman(CDH) problem is to compute \(DH_{g}(h_{1},h_{2})\) for uniform \(h_1\) and \(h_2\). It is not clear whether hardness of the discrete-logarithm problem implies that the CDH problem is hard as well.

The decisional Diffie-Hellman(DDH) problem is, when given uniform \(h_{1},h_{2}\) and a third group element \(h'\), distinguish whether \(h'=DH_{g}(h_{1},h_{2})\) or \(h'\) is chosen from a uniform group element.

RSA generation

Key management evolution

key distribution in private-key encryption

Problems

- Key distribution: The key must be shared through a secure channel.

- Storing and managing large number of secret keys: N people communicating with each other need to store N-1 secret keys for each one.

- Inapplicability of private-key cryptography to open systems: can not interact with new users.

Key-distribution centers

A key-distribution center(KDC) can become a partial solution for the problem above. An entity trusted by all the users serves as a key-distribution center and it helps all the users share pairwise keys.

Offline fashion: When a new people \(i\) join, the KDC shares a key with this people, and also distributes \(n-1\) shared keys between \(i\) and other \(1\sim i-1\) people.

Online fashion: Generate key on demand whenever Alice and Bob need to communicate securely. Choose a new, random key \(k\), then send to Alice encrypted using \(k_{A}\) and to Bob encrypted using \(k_{B}\). (\(k_{A}\) is a private key between KDC and Alice)

The KDC can alleviate two of the problem: the key distribution is simplified, and the key storage is eased.

There are also some drawbacks: the KDC is a single point of failure, and a successful attack on the KDC will result in a complete break of the system.

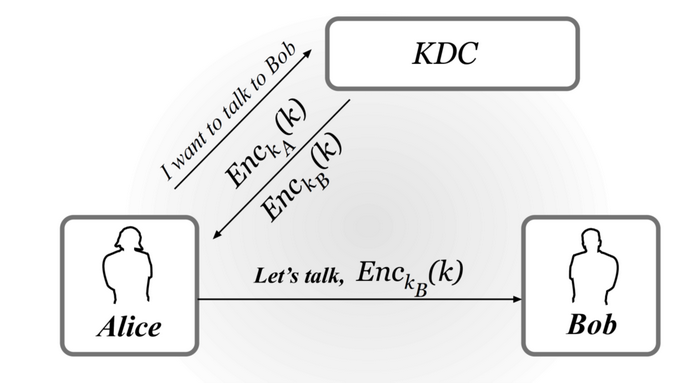

Needham-Schroder protocol

A protocol for secure key distribution using KDC. One of its features is that KDC sends to Alice the session key encrypted under Alice's key in addition to the session key encrypted under Bob's key. Alice then sends the second ciphertext to Bob as a credential that allows Alice talk to Bob.

The process is shown as the following figure:

Diffie-Hellman protocol

The KDC approaches still require a private and authenticated channel that can be used to share keys, so it is still not applicable in open systems.

Diffie and Hellman's paper stated that there are certain actions that can be easily performed but not easily reversed. This phenomena could be used to derive interactive protocols for sercure key exchange that allow two parties to share a secret key via communication over a public but authenticated channel, by having the parties perform operations that they can reverse but that an eavesdropper cannot.

Secure key exchange

The key-exchange experiment \(KE_{\mathcal{A},\pi}^{eav}(n)\):

Two parties holding \(1^n\) execute protocol \(\Pi\). This results in a transcript \(trans\) containing all the messages sent by the parties, and a key \(k\) output by each of the parties.

A uniform bit \(b\in \{0,1\}\) is chosen. If \(b=0\) set \(\hat{k}:=k\), and if b=1 then choose \(\hat{k}\in \{0,1\}^{n}\) uniformly at random

\(\mathcal{A}\) is given \(trans\) and \(\hat{k}\), and output a bit \(b'\)

The output of the experiment is defined to be 1 if \(b'=b\) and 0 otherwise. In the case that \(KE_{\mathcal{A},\pi}^{eav}(n)=1\) we say that \(\mathcal{A}\) succeeds.

A key-exchange protocol \(\Pi\) is secure in the presence of an eavesdropper if for all probabilistic polynomial-time adversaries \(\mathcal{A}\) there is a negligible function \(negl\) such that \[ Pr[KE_{\mathcal{A},\pi}^{eav}(n)=1]\le \frac{1}{2}+negl(n) \]

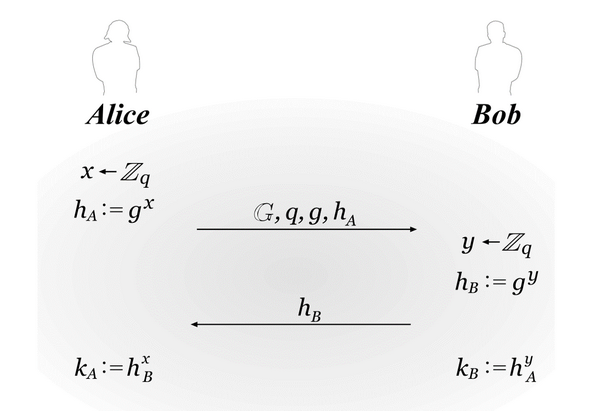

The Diffie-Hellman key-exchange protocol

Let \(\mathcal{G}\) be a probabilistic polynomial-time algorithm that, on input \(1^n\), outputs a description of a cyclic group \(\mathbb{G}\), its order \(q\) with \(||q||=n\), and a generator \(g\in \mathbb{G}\). The Diffie-Hellman key-exchange protocol can be described as follows:

- Common input: The security parameter \(1^n\).

- The protocol:

- Alice runs \(\mathcal{G}(1^{n})\) to obtain \((\mathbb{G},q,g)\).

- Alice chooses a uniform \(x\in \mathbb{Z}_{q}\), and computes \(h_{A}:=g^x\).

- Alice sends \((\mathbb{G},q,g,h_{A})\) to Bob.

- Bob receives \((\mathbb{G},q,g,h_{A})\). He chooses a uniform \(y\in \mathbb{Z}_{q}\), and computes \(h_{B}:=g^y\). Bob sends \(h_{B}\) to Alice and outputs the key \(k_{B}:=h_{A}^{y}\).

- Alice receives \(h_{B}\) and outputs the key \(k_{A}:=h_{B}^{x}\).

The following figure illustrate the construction of Diffie-Hellman key-exchange protocol:

If the decisional Diffie-Hellman problem is hard relative to \(\mathcal{G}\), then the Diffie-Hellman key-exchange protocol \(\Pi\) is secure in the presence of an eavesdropper.

Please note that the shared key is indistinguishable from a uniform element of \(\mathbb{G}\) rather than from a uniform n-bit string.

In order to use the key for subsequent cryptographic applications, the key output by the parties should be indistinguishable from a uniform bit-string of the appropriate length. The Diffie-Hellman protocol can be modified to achieve this by using an appropriate key-derivation function.

Diffie-Hellman protocol is completely insecure against man-in-the-middle attacks (both honest parties are executing the protocol and the adversary is intercepting and modifying messages being sent from one party to the other). But it is the core of standardized key-exchange protocols today.

Public-key encryption

Overview

In public-key encryption, the receiver generates a pair of keys \((pk,sk)\), called the public key and private key respectively. The public key is used by the sender to encrypt a message; the receiver uses the private key to decrypt the resulting ciphertext.

Two ways to learn \(pk\) (Alice is the receiver and Bob is the sender):

When Alice learns that Bob wants to communicate with her, generate \((pk,sk)\) and then send \(pk\) to Bob in the clear.

Alice generate her keys \((pk,sk)\) in advance, independently of any particular sender. Then she can widely disseminate \(pk\) so that anyone who wishes to communicate with her can use \(pk\) directly.

Some important notes for public-key encryption:

- The security of public-key encryption relies on the secrecy of \(sk\).

- The security of public-key encryption is under the assumption that the sender are able to obtain a legitimate copy of the receiver's public key.

Comparison with private-key encryption:

- Advantages:

- The key-distribution could be done over public but authenticated channels, since \(pk\) do not need to be secret.

- Reduce the need for users to store many secret keys.

- More suitable for open environments.

- Drawbacks:

- The receiver could receive messages from anyone. (When receiver only wants to receive the message from specific invididuals it is a drawback).

- Roughly 2 to 3 orders of magnitude slower than private-key encryption.

Public-key encryption scheme

A public-key encryption scheme is a triple of probabilistic polynomial-time algorithms \((Gen,Enc,Dec)\) such that:

- The key-generation algorithm \(Gen\) takes the security parameter \(1^n\) as input and outputs a pair of keys \((pk,sk)\). We refer to the first of these as the public key and the second as private key. Assuming for convenience that \(pk\) and \(sk\) each has length at least \(n\), and \(n\) can be determined from \(pk,sk\).

- The encryption algorithm \(Enc\) takes a public key \(pk\) and a message \(m\) from some message space (depend on \(pk\)) as input. It outputs a ciphertext \(c\), and we write it as \(c\leftarrow Enc_{pk}(m)\). (Write this way means that \(Enc\) is probabilistic, which is needed to achieve meaningful security)

- The deterministic decryption algorithm \(Dec\) takes a private key \(sk\) and a ciphertext \(c\) as input, and outputs a message \(m\) or a special symbol denoting failure. We write this as \(m:=Dec_{sk}(c)\).

KEM/DEM paradigm

Hybrid encryption

In hybrid encryption, both private-key encryption and public-key encryption are used. The aims of using hybrid encryption:

- Private-key encryption can increase efficiency.

- Using public-key encryption to increase bandwidth.

Note that although the private-key encryption is used as a component, this method still belongs to public encryption schemes, since the sender and receiver do not share any secret key in advance.

Construction

A key-encapsulation mechanism(KEM) is a tuple of probabilistic polynomial-time algorithms \((Gen,Encaps,Decaps)\) such that:

The key-generation algorithm \(Gen\) takes as input the security parameter \(1^n\) and outputs a public-/private-key pair \((pk,sk)\). Assuming that \(pk\) and \(sk\) each has length at least \(n\), and \(n\) can be determined from \(pk,sk\).

The encapsulation algorithm \(Encaps\) takes as input a public key \(pk\) and the security parameter \(1^n\). It outputs a ciphertext \(c\) and a key \(k\in \{0,1\}^{\ell (n)}\) where \(\ell\) is the key length. It can be written as \((c,k)\leftarrow Encaps_{pk}(1^{n})\).

The deterministic decapsulation algorithm \(Decaps\) takes as input a private key \(sk\) and a ciphertext \(c\), and outputs a key \(k\) or a special symbol denoting failure. We write this as \(k:=Decaps_{sk}(c)\).

By using a KEM, a key \(k\) is generated and then is used for private-key encryption. The private-key encrypton scheme is called the data-encapsulation mechanism(DEM).

Using the construction above, we can construct hybrid encryption using the KEM/DEM paradigm:

Let \(\Pi=(Gen,Encaps,Decaps)\) be a KEM with key length \(n\), and let \(\Pi'=(Gen',Enc',Dec')\) be a private-key encryption scheme. Construct a public-key encryption scheme \(\Pi^{hy}=(Gen^{hy},Enc^{hy},Dec^{hy})\) as follows:

- \(Gen^{hy}\): on input \(1^n\) run \(Gen(1^{n})\) and use the public and private keys \((pk,sk)\) that are output.

- \(Enc^{hy}\): on input a public key \(pk\) and a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^*\) do:

- Compute \((c,k)\leftarrow Encaps_{pk}(1^n)\).

- Compute \(c'\leftarrow Enc_{k}^{'}(m)\).

- Output the ciphertext \(<c,c'>\).

- \(Dec^{hy}\): on input a private key \(sk\) and a ciphertext \(<c,c'>\) do:

- Compute \(k:=Decaps_{sk}(c)\).

- Output the message \(m:=Dec_{k}^{'}(c')\).

CDH/DDH-based encryption

El Gamal encryption

Let \(\mathcal{G}\) be a probabilistic polynomial-time algorithm that, on input \(1^n\), outputs a description of a cyclic group \(\mathbb{G}\), its order \(q\) with \(||q||=n\), and a generator \(g\in \mathbb{G}\). Define the El Gamal encryption scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\) run \(\mathcal{G}(1^{n})\) to obtain \((\mathbb{G},q,g)\). Then choose a uniform \(x\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and compute \(h:=g^x\). The public key is \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,h>\) and the private key is \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,x>\). The message space is \(\mathbb{G}\).

- \(Enc\): on input a public key \(pk=<\mathbb{G},q,g,h>\) and a message \(m\in \mathbb{G}\), choose a uniform \(y\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and output the ciphertext \(<g^{y},h^{y}\cdot m>\).

- \(Dec\): on input a private key \(sk=<\mathbb{G},q,g,x>\) and a ciphertext \(<c_{1},c_{2}>\), output \(\hat{m}:=c_{2}/c_{1}^{x}\).

If the DDH problem is hard relative to \(\mathcal{G}\), then the El Gamal encryption scheme is CPA-secure, but it is not CCA-secure!

Some implementation issues:

- It is common for these parameters generated by \(Gen\) to be fixed once for all, and then shared by multiple receivers. Sharing parameters in this way does not impact security.

- The group order \(q\) is generally chosen to be prime. And elliptic curves are one popular choice.

- The message space is a group \(\mathbb{G}\) rather than bit-strings. So the messages need to be encoded as group elements before encryption, and decoded after decryption.

DDH-based key encapsulation

Let \(\mathcal{G}\) be a probabilistic polynomial-time algorithm that, on input \(1^n\), outputs a description of a cyclic group \(\mathbb{G}\), its order \(q\) with \(||q||=n\), and a generator \(g\in \mathbb{G}\). Define a KEM as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\) run \(\mathcal{G}(1^{n})\) to obtain \((\mathbb{G},q,g)\). Then choose a uniform \(x\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and compute \(h:=g^x\). Also specify a function \(H:\mathbb{G}\rightarrow \{0,1\}^{\ell (n)}\) for some function \(\ell\). The public key is \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,h,H>\) and the private key is \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,x>\).

- \(Encaps\): on input a public key \(pk=<\mathbb{G},q,g,h,H>\), choose a uniform \(y\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and output the ciphertext \(g^{y}\) and the key \(H(h^{y})\).

- \(Decaps\): on input a private key \(sk=<\mathbb{G},q,g,x>\) and a ciphertext \(c\in \mathbb{G}\), output the key \(H(c^{x})\).

If the gap-CDH problem (based on CDH problem, additionally give access to an oracle \(\mathcal{O}\) that \(\mathcal{O}(U,V)\) returns 1 when \(V=U^y\)) is hard relative to \(\mathcal{G}\), and \(H\) is modeled as a random oracle (an ideal model that treats a cryptographic hash function \(H\) as a truly random function), then the above construction is a CCA-secure KEM.

DHIES/ECIES

Let \(\mathcal{G}\) be a probabilistic polynomial-time algorithm that, on input \(1^n\), outputs a description of a cyclic group \(\mathbb{G}\), its order \(q\) with \(||q||=n\), and a generator \(g\in \mathbb{G}\). Let \(\Pi_{E}=(Enc',Dec')\) be a private-key encryption scheme, and let \(\Pi_{M}=(Mac,Vrfy)\) be a message authentication code. Define a public-key encryption scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): On input \(1^n\) run \(\mathcal{G}(1^{n})\) to obtain \((\mathbb{G},q,g)\). Choose a uniform \(x\in \mathbb{Z}_q\), set \(h:=g^x\), and specify a function \(H:\mathbb{G}\rightarrow \{0,1\}^{2n}\). The public key is \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,h,H>\) and the private key is \(<\mathbb{G},q,g,x,H>\).

- \(Enc\): On input a public key \(pk=<\mathbb{G},q,g,h,H>\), choose a uniform \(y\in \mathbb{Z}_q\) and set \(k_{E}||k_{M}:=H(h^{y})\). Compute \(c'=Enc_{k_{E}}^{'}(m)\) and output the ciphertext \(<g^{y},c',Mac_{k_{M}}(c')>\).

- \(Dec\): On input a private key \(sk=<\mathbb{G},q,g,x,H>\) and a ciphertext \(<c,c',t>\), output failure if \(c\notin \mathbb{G}\). Else, compute \(k_{E}||k_{M}:=H(c^{x})\). If \(Vrfy_{k_{M}}(c',t)\ne 1\) then output failure, otherwise output \(Dec_{k_{E}}^{'}(c')\).

When the group \(\mathbb{G}\) is a cyclic subgroup of a finite field, this encryption scheme is called the Diffie-Hellman Integrated Encryption Scheme (DHIES). And When \(\mathbb{G}\) is an elliptic-curve group, it is called the Elliptic Curve Integrated Encryption Scheme (ECIES).

Let \(\Pi_{E}\) be a CPA-secure private-key encryption scheme, and let \(\Pi_{M}\) be a strongly secure message authentication code. If the gap-CDH problem is hard relative to \(\mathcal{G}\), and \(H\) is modeled as a random oracle, then the above construction is a CCA-secure public-key encryption scheme.

RSA encryption

Plain RSA

Using RSA generation algorithm , define the plain RSA encryption scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\) run \(GenRSA(1^{n})\) to obtain \(N\), \(e\) and \(d\). The public key is \(<N,e>\) and the private key is \(<N,d>\).

- \(Enc\): on input a public key \(pk=<N,e>\) and a message \(m\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), compute the ciphertext \(c:=[m^{e}~mod~N]\)

- \(Dec\): on input a private key \(sk=<N,d>\) and a ciphertext \(c\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), compute the message \(m:=[c^{d}~mod~N]\).

Plain RSA encryption is deterministic and so it is not CPA-secure!

Padded RSA & PKCS #1 v1.5

Using RSA generation algorithm, and let \(\ell\) be a function with \(\ell (n)\le 2n-4\) for all \(n\). Define a public-key encryption scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\) run \(GenRSA(1^{n})\) to obtain \(N\), \(e\) and \(d\). The public key is \(<N,e>\) and the private key is \(<N,d>\).

- \(Enc\): on input a public key \(pk=<N,e>\) and a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^{||N||-\ell (n)-2}\), choose a uniform string \(r\in \{0,1\}^{\ell (n)}\) and interpret \(\hat{m}:=r||m\) as an element of \(\mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\). Output the ciphertext \(c:=[\hat{m}^{e}~mod~N]\).

- \(Dec\): on input a private key \(sk=<N,d>\) and a ciphertext \(c\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), compute \(\hat{m}:=[c^{d}~mod~N]\) and output the \(||N||-\ell (n)-2\) least-significant bits of \(\hat{m}\).

The RSA laboratories Public-Key Cryptography Standard (PKCS) #1 version 1.5, utilizes a varient of padded RSA encryption. Let \(k\) denote an integer satisfying \(2^{8(k-1)}\le N \le 2^{8k}\) (the length of \(N\) in bytes). Messages \(m\) to be encrypted are assumed to be a multiple of 8 bits long and can have length anywhere from one to \(k-11\) bytes. Encryption of a message \(m\) is computed as \([(0x00||0x02||r||0x00||m)^{e}~mod~N]\), where \(r\) is randomly generated.

Unfortunately, PKCS #1 v1.5 as specified is not CPA-secure because it allows using random padding that is too short. If we force \(r\) to be roughly half the length of \(N\), then it is reasonable to conjecture that the encryption scheme in PKCS #1 v1.5 is CPA-secure. Also, PKCS #1 v1.5 is not CCA-secure.

OAEP & RSA PKCS #1 v2.0

Let \(GenRSA\) be as in the previous sections, and \(\ell(n),k_{0}(n),k_{1}(n)\) be integer-valued functions with \(k_{0}(n),k_{1}(n)=\Theta(n)\) and that \(\ell(n)+k_{0}(n)+k_{1}(n)\) is less than the minimum bit-length of moduli output by \(GenRSA(1^{n})\). Let \(G:\{0,1\}^{k_{0}}\rightarrow \{0,1\}^{\ell+k_{1}}\) and \(H:\{0,1\}^{\ell+k_{1}}\rightarrow \{0,1\}^{k_{0}}\) be functions. Construct the RSA-OAEP encryption scheme as follows:

- \(Gen\): on input \(1^n\) run \(GenRSA(1^{n})\) to obtain \(N\), \(e\) and \(d\). The public key is \(<N,e>\) and the private key is \(<N,d>\).

- \(Enc\): on input a public key \(<N,e>\) and a message \(m\in \{0,1\}^{\ell}\), set \(m':=m||0^{k_{1}}\) and choose a uniform \(r\in \{0,1\}^{k_{0}}\). Then compute \(s:=m'~XOR~G(r)\), \(t:=r~XOR~H(s)\), and set \(\hat{m}:=s||t\). Output the ciphertext \(c:=[\hat{m}^{e}~mod~N]\).

- \(Dec\): on input a private key \(<N,d>\) and a ciphertext \(c\in \mathbb{Z}_{N}^{*}\), compute \(\hat{m}:=[c^{d}~mod~N]\). If \(||\hat{m}||>\ell +k_{0}+k_{1}\), output error. Otherwise, parse \(\hat{m}\) as \(s||t\) with \(s\in \{0,1\}^{\ell+k_{1}}\) and \(t\in \{0,1\}^{k_{0}}\). Compute \(r:=H(s)~XOR~t\) and \(m':=G(r)~XOR~s\). If the least-significant \(k_1\) bits of \(m'\) are not all 0, output error. Otherwise, output the \(\ell\) most-significant bits of \(\hat{m}\).

The RSA-OAEP encryption scheme is CCA-secure. But the encryption scheme should ensure that the time to return an error is identical regardless of where the error occurs, otherwise this information can be used as side-channel information in CCA.

Recommended key lengths

References

- Jonathan Katz, Yehuda Lindell. Introduction to Modern Cryptography, Second Edition.

- https://baike.baidu.com/item/SM2/15081831?fr=aladdin

- https://blog.csdn.net/BlackNight168/article/details/88169642

- https://blog.csdn.net/samsho2/article/details/80772228