Basic concepts

What is cryptography?

The study of mathematical techniques for securing digital information, systems, and distributed computations against adversarial attacks.

Category

- private(symmetric) key encryption: encryption and decryption use the same key.

- public(asymmetric) key encryption: encryption and decryption use different keys.

Kerckhoffs' principle

Kerckhoffs' principle: The cipher method must not be required to be secret, and it must be able to fall into the hands of the enemy without inconvenience.

Security rely solely on secrecy of the key!

Three primary arguments in favor of Kerckhoffs' principle:

- It's significantly easier for the parties to maintain secrecy of a short key than to keep secret the encryption/decryption algorithm.

- In case the secret information is ever exposed, it will be much easier to change a key than to replace an encryption scheme.

- It's significantly easier for users to all rely on the same encryption algorithm. i.e. The encryption schemes should be standardize so that (1) compatibiity is ensured (2) encryption scheme could undergone public scrutiny.

Historical ciphers

Casear's cipher (shift cipher)

Casear's cipher: Shifting the letters of the alphabet \(n\) bits forward. At the end of the alphabet, the letters wrap around. \[ Enc_{k}(m_{1}\dots m_{l})=c_{1}\dots c_{l}, c_{i}=[(m_{i}+k)mod 26] \] \[ Dec_{k}(c_{1}\dots c_{l})=m_{1}\dots m_{l}, m_{i}=[(c_{i}-k)mod 26] \] So it can be decrypted effortlessly(Just try by brute force).

e.g. encrypt begin the attack now\(\rightarrow\) EHJLQWKHDWWDFNQRZ

Application: Online forums. It is used merely to ensure the text is unintelligible unless the reader consciously chooses to decrypt it.

What can we learn from that?

Sufficient key-space principle: Any secure encryption scheme must have a key space that is sufficiently large to make an exhaustive-search attack infeasible.

Attention: the sufficient key-space principle gives a necessary condition for security, but not a sufficient one.

Mono-alphabetic substitution cipher

Mono-alphabetic substitution cipher: The key defines a map from each letter of the plaintext alphabet to some letter of the cipher text alphabet, where the map is arbitrary as long as that it be one-to-one.

The key space consists of all bijections(permutations) of the alphabet.

tellhimaboutme \(\rightarrow\) GDOOKVCXEFLGCD

The key space is of size \(26!\approx 2^{88}\), which means that the brute force attack is infeasible. But is that safe?

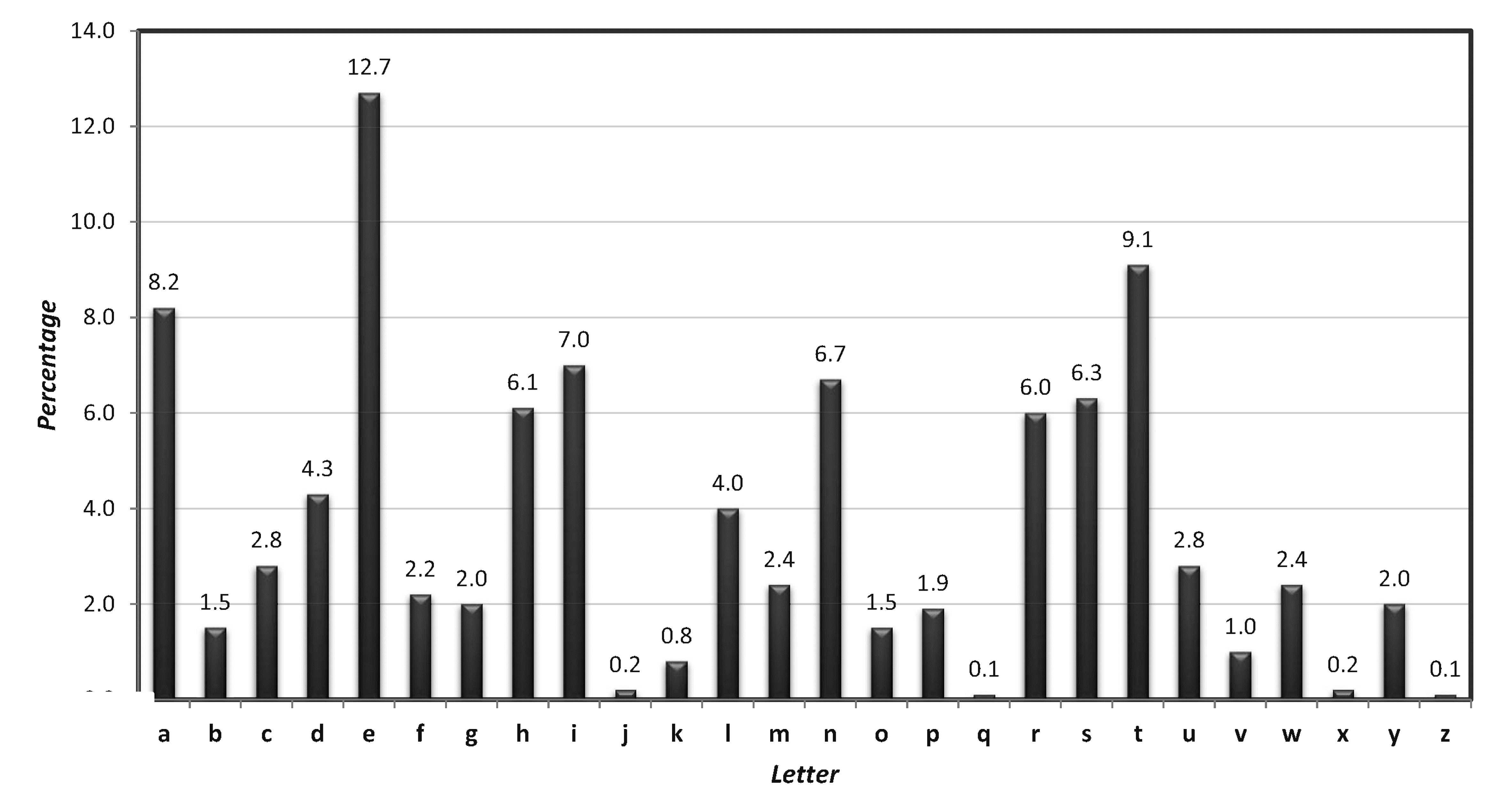

Based on the letter frequency distribution in the following figure,

let \(p_{i}\) denote the frequency of the \(i\)th letter in the English text, we can get the following result: \[ \sum_{i=0}^{25}p_{i}^{2}\approx 0.065 \] Attack on the Mono-alphabetic substitution cipher relies on the fact that the frequency distribution of individual letters in the English language is known.

The mono-alphabetic substitution cipher is still insecure, even if it has large key space!

Poly-alphabetic substitution cipher

Poly-alphabetic substitution cipher: The key defines a mapping that is applied on blocks of plaintext characters.

E.g.: A special case called The Vigenere cipher

Poly-alphabet substitution ciphers "smooth out" the frequency distribution of characters in the ciphertext, which makes it harder to perform statistical analysis. A systematic attack on this scheme was only devised hundreds of years later after this cipher was invented.

If we know the length of the key, then the attack is relatively easy. Assuming the key \(k=k_{1}\dots k_{t}\), then the ciphertext can be divided into \(t\) parts where each part can be seen as having been encrypted using a shift cipher, which is easy to decrypt. But what if the key length is unknown?

Some methods for determining the key length:

If the maximum length \(T\) of the key is not too large, we can just use brute force.

Kasiski's method.

Find the repeated patterns of length 2 or 3 in the ciphertext first(likely to be certain bigrams or trigrams, e.g. the, am, is, are, that appears frequently). The distance between them must be a multiple of the period \(t\). Then we can get \(gcd(l_{1}, l_{2}\dots l_{n})=kt\)

Index of coincidence method

Recall that if the key length is \(t\), then in the ciphertext characters \(c_{1}, c_{1+t}, c_{1+2t}, \dots\) all resulted from encryption using same shift.

Let \(q_{i}\) denote the observed letter frequency of the \(i\)th English letter in the above stream, from equation of english letter frequency we can get: \[ \sum_{i=0}^{25}q_{i}^{2}\approx \sum_{i=0}^{25}p_{i}^{2}\approx 0.065 \] So, for \(\tau =1, 2, \dots\), just look at sequence of ciphertext characters \(c_{1}, c_{1+\tau}, c_{1+2\tau}, \dots\) and calculate \(q_{0}, \dots, q_{25}\). Then compute \(S_{\tau} \xlongequal{def}\sum_{i=0}^{25}q_{i}^{2}\)

When \(\tau=t\) we expect \(S_{\tau}\approx 0.065\), else we expect that all characters will occur with roughly equal probablity and \(S_{\tau}\approx \sum_{i=0}^{25}(\frac{1}{26})^{2}\approx 0.038\)

What can we learn: A longer key means harder to attack.

Conclusion

Desiging secure ciphers is hard!

Principles of modern cryptography

Formal definitions

If you don't understand what you want to achieve, how can you possibly know when or if you have achieved it?

Considering what threats are in scope and what security guarantees are desired. Then we can find an encryption scheme satisfying the demands. A side benefit: modularity.

A secure definition has two components:

- A security guarantee: what the scheme is intended to prevent the attack from doing.

- Threat model: what actions that attacker is assumed able to carry out.

A secure encryption scheme should guarantee that a ciphertext should leak no additional information about the underlying plaintext regardless of any information an attacker already has.

Precise assumptions

The most modern cryptographic constructions cannot be proven secure unconditionally, since the proofs of their security rely on assmuptions. Any assumption is required to be made explicit and mathematically precise.

Proofs of security

The two principles described above allow us to provide a rigorous proof that a construction satisfies a given definition under certain specified assumptions. Proofs of security give an iron-clad guarantee that no attacker will succeed.

Threats

Assumptions:

- The attackers know the encryption algorithm.

- The attackers can use any strategy to attack.

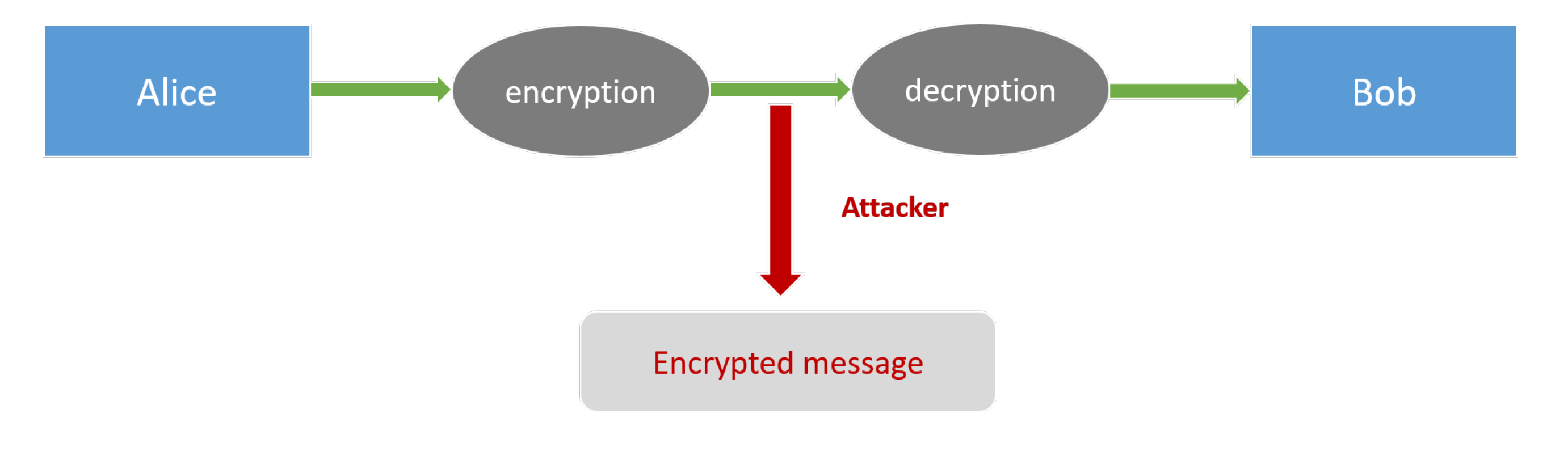

Ciphertext-only attack

The adversary just observes a ciphertext. The adversary attempts to determine information about the underlying plaintexts.

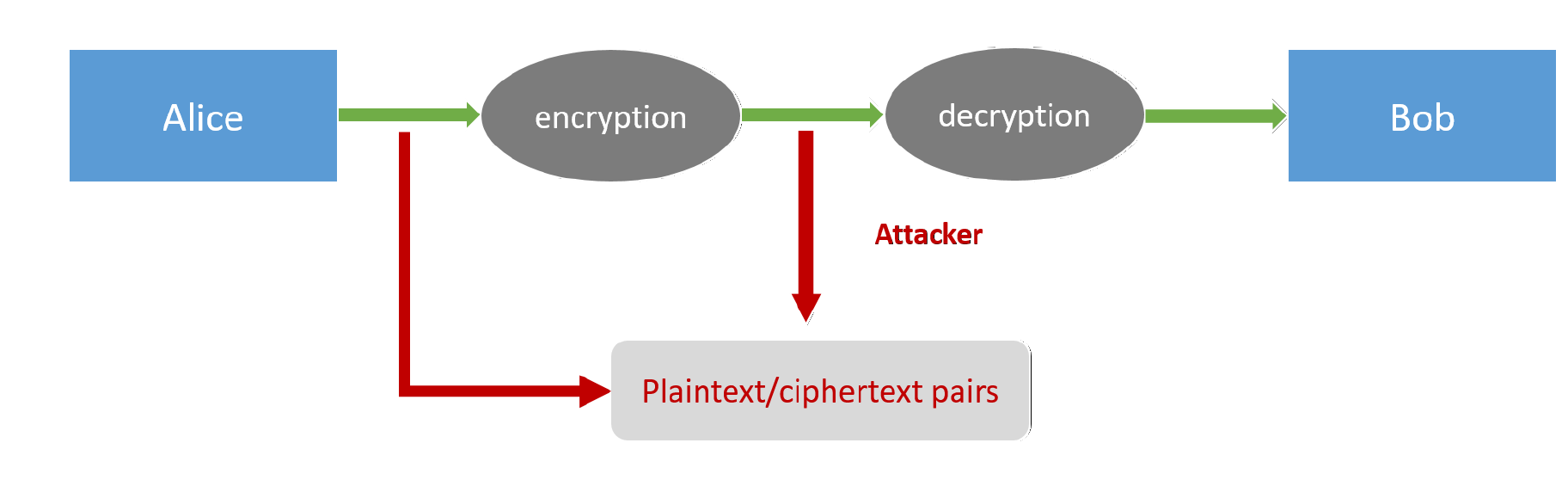

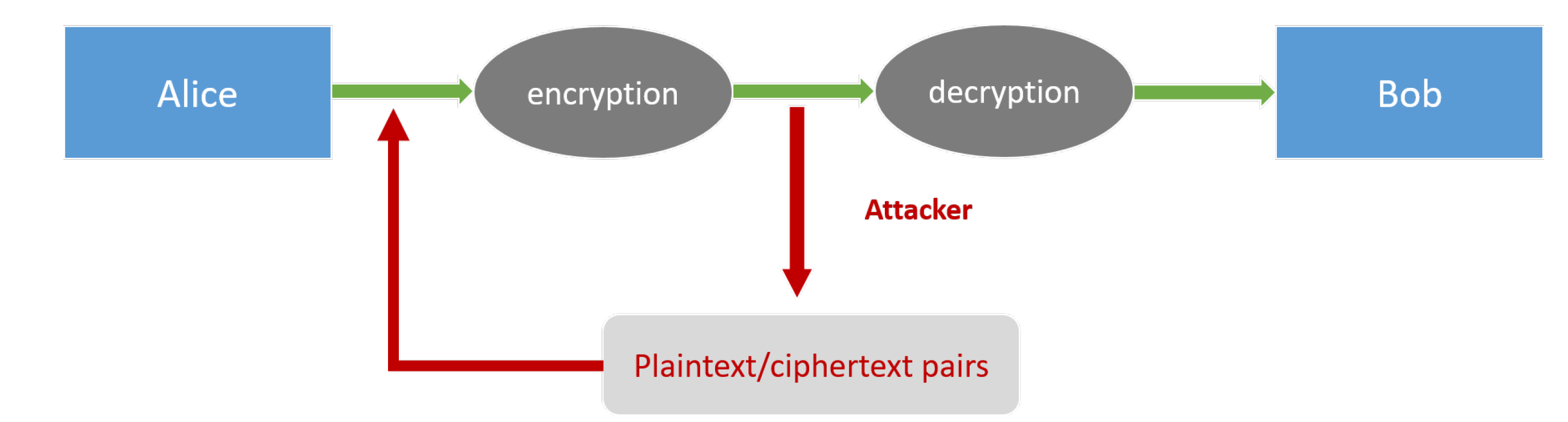

Known-plaintext attack

The adversary is able to learn one or more plaintext/ciphertext pairs generated using the same key.

The aim of the adversary is to deduce information about the underlying plaintext of some other ciphertext produced using the same key.

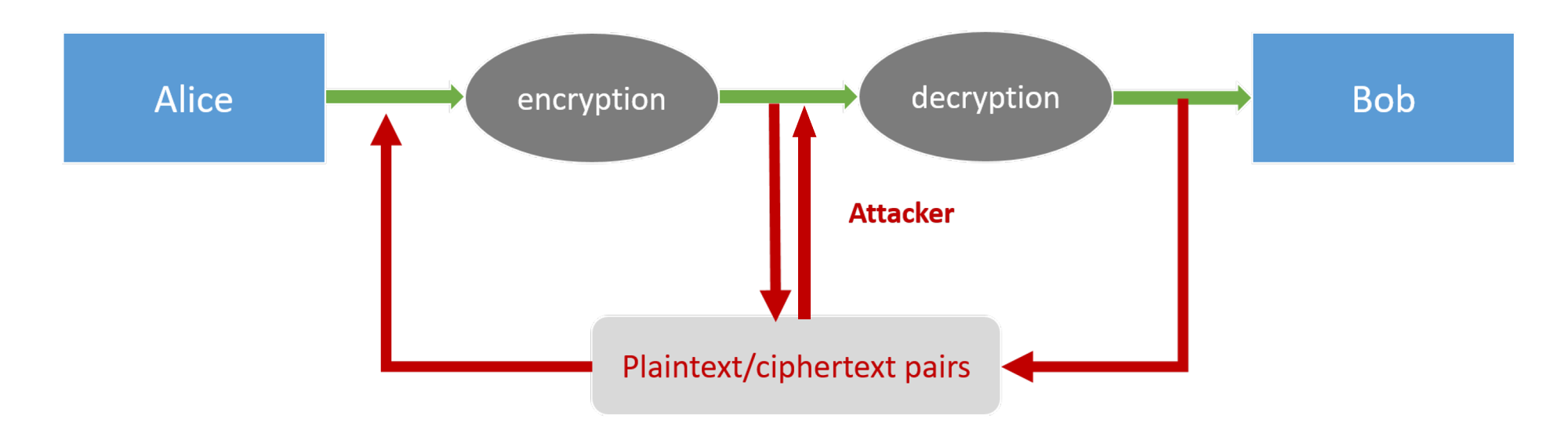

Chosen-plaintext attack

The adversary can obtain plaintext/ciphertext pairs for plaintexts of its choice.

Chosen-ciphertext attack

The adversary is able to additionally(compared with chosen-plaintext attack) obtain the decryption of ciphertexts of its choice.

The adversary's aim is to learn information about the underlying plaintext of some other ciphertext(whose decryption the adversary is unable to obtain directly).

Perfect secrecy

Randomness

Randomness is essential in cryptography!

Steps for generating random numbers:

Collect a "pool" of high-entropy data. E.g. external inputs(mouse movements, hard-disk access times, etc.), system hardware(thermal/shot noise, etc.)

The high-entropy data is processed to yield a sequence of nearly independent and unbias bits(The raw high-entropy data might not be uniformally distributed).

A poor random-number generators could make a good cryptosystem vulnerable to attack. E.g. the rand() function in C stdlib.h libaray is cryptographically insecure.

Principle: use a random-number generator designed for cryptographic use.

Perfect secrecy

Definition: an encryption scheme (Gen, Enc, Dec) with message space \(\mathcal{M}\) is perfectly secret if for every probability distribution over \(\mathcal{M}\), every message \(m\in \mathcal{M}\), and every ciphertext \(c\in \mathcal{C}\) for with \(Pr[C=c]>0\): \[ Pr[M=m|C=c]=Pr[M=m] \] An equivalent formulation: an encryption scheme (Gen, Enc, Dec) with message space \(\mathcal{M}\) is perfectly secret if and only if the following equation holds for every \(m, m'\in \mathcal{M}\), and every \(c\in \mathcal{C}\): \[Pr[Enc_{K}(m)=c]=Pr[Enc_{K}(m')=c]\]

Another definition based on the adversarial indistinguishability experiment \(PrivK_{\mathcal{A},\pi}^{eav}\) (eav means eavesdropper, i.e. the attacker \(\mathcal{A}\) only knows the ciphertext):

The adversary \(\mathcal{A}\) outputs a pair of messages \(m_{0}, m_{1}\in \mathcal{M}\). Note that the messages are randomly chosen so \(|m_{0}|\) and \(|m_{1}|\) might be different.

A key \(k\) is generated using Gen, and a uniform bit \(b\in \{0, 1\}\) is chosen (i.e. \(m_0\) or \(m_1\) are chosen with probability \(\frac{1}{2}\)). Challenge ciphertext \(c\leftarrow Enc_{k}(m_{b})\) is computed and given to \(\mathcal{A}\).

\(\mathcal{A}\) outputs a bit \(b'\). Note that no computation power is limited to \(\mathcal{A}\).

The output of the experiment is 1 if \(b'=b\), and 0 otherwise. We say \(PrivK_{\mathcal{A},\pi}^{eav}=1\) if the output of the experiment is 1 and in this case we say that \(\mathcal{A}\) succeeds.

Encryption scheme \(\Pi=(Gen, Enc, Dec)\) with message space \(\mathcal{M}\) is perfectly indistinguishable if for every \(\mathcal{A}\) it holds that \[ Pr[PrivK_{\cal{A},\pi}^{eav}=1]=\frac{1}{2} \text{(i.e. random guess)} \] And encryption scheme \(\Pi\) is perfectly secret if and only if it is perfectly indistinguishable.

In a word, perfect secrecy means the probability distribution of the ciphertext does not depend on the plaintext.

One-time pad

Construction of one-time pad encryption:

Fix an integer \(\ell >0\). The message space \(\mathcal{M}\), key space \(\mathcal{K}\) and ciphertext space \(\mathcal{C}\) are all equal to \(\{0, 1\}^{\ell}\)(the set of all binary strings with length \(\ell\)). The one-time pad encryption is constructed as follows:

- \(Gen\): the key-generation algorithm chooses a key from \(\mathcal{K}=\{0, 1\}^{\ell}\) according to uniform distribution. (i.e. each of the \(2^{\ell}\) strings in the space is chosen with equal probability \(2^{-\ell}\)).

- \(Enc:\) given a key \(k\in \{0, 1\}^{\ell}\) and a message \(m\in \{0, 1\}^{\ell}\), the encryption algorithm outputs the ciphertext \(c:=k\text{ XOR }m\).

- \(Dec\): given a key \(k\in \{0, 1\}^{\ell}\) and a ciphertext \(c\in \{0, 1\}^{\ell}\), the decryption algorithm outputs the message \(m:=k\text{ XOR }c\) (\(a\text{ XOR }b\text{ XOR }b=a\)).

The one-time pad encryption scheme is perfectly secret. But the most prominent drawback is that the key is as long as the message.

Moreover, the one-time pad is only secure if used once(just as the name indicates). E.g., if two messages \(m, m'\) are encrypted using the same key \(k\), an adversary who obtains \(c, c'\) can compute \(c\text{ XOR }c'=m\text{ XOR }m'\) and thus learn where the two messages differ(information leakage).

limitations of perfect secrecy: if \(\Pi=(Gen, Enc, Dec)\) is a perfectly secret encryption scheme with message space \(\mathcal{M}\) and key space \(\mathcal{K}\), then \(|\mathcal{K}|\ge |\mathcal{M}|\).

References

- Jonathan Katz, Yehuda Lindell. Introduction to Modern Cryptography, Second Edition.